By Dr. Seleem R. Choudhury, October 13, 2021

Nearly half of all Americans suffer from at least one chronic disease, and that number is growing (American Association of Retired Persons; Fried, 2017; Tinker, 2017). Chronic diseases—including cancer, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, heart disease, respiratory diseases, arthritis, obesity, and oral diseases—can lead to hospitalization, long-term disability, reduced quality of life, and death. Additionally, chronic diseases often require a long period of supervision, observation, or care (Rothman, & Wagner, 2003). To make matters more complicated, many patients have multiple morbidities, creating particular challenges for healthcare providers (Braillard, Slama-Chaudhry, Joly, Perone, & Beran, 2018).

As Reynolds, et al, explain in their 2018 article, “the defining features of primary care (including continuity, coordination, and comprehensiveness) makes this setting suitable for managing chronic conditions” (Reynolds, Dennis, Hasan, Slewa, Chen, et al., 2018). High-performing primary care teams keep the “quadruple aim” of primary care—enhancing the care experience, improving the health of the population, reducing costs, and improving the work-life of the team—at the forefront of their work (Haverfield, Tierney, Schwartz, Bass, Brown-Johnson, et al, 2020). Studies repeatedly bear this out, demonstrating that an integrated approach with an aim to improve the quality of life of patients—as well as those caring for them—can enhance chronic disease outcomes and management. As the healthcare industry continues to evolve, it cannot afford not to invest in primary care.

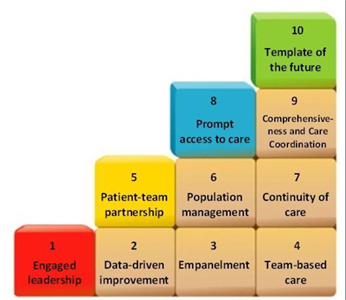

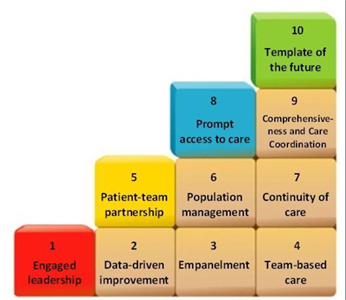

Bodenheimer’s Building Blocks

Current literature discussing characteristics of best primary care practices supports three well-proven methods:

- Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) standards from the National Committee on Quality Assurance (Hahn, Gonzalez, Etz, & Crabtree, 2014),

- the Peterson Center on Health Care’s “America’s Most Valuable Care: Primary Care” (Peterson Center on Health Care, & Stanford Medicine Clinical Excellence Research Center, 2014), and

- the Building Blocks framework commonly known as Bodenheimer’s Building Blocks. (Bodenheimer, Ghorob, Willard-Grace, & Kevin Grumbach, 2014).

Each of these models is similar, often reinforcing one another yet each with its unique benefits. Inspired by a conversation with Tanya Kapka, MD, MPH, FAAFP, a leader in healthcare transformation, this article will focus on four specific areas within Bodenheimer’s Building Blocks: Engaged Leadership, Data-Driven Improvement, Empanelment, and Team-Based Care (see graphic). These four blocks are foundational in the quest for clinical excellence in primary care.

Block 1: Engaged leadership

One of the most commonly cited reasons for failed PCMH change efforts is a lack of leadership support (Qureshi, Quigley, & Hays, 2020). Active, engaged, supportive leadership is not a new necessity, nor is its importance limited to healthcare. The role is critical in Comprehensive Primary Care transformation (Altman Dautoff, Philips, & Manning, 2013). Leaders are the ones who drive and inspire change. Without a leader to champion the change and navigate teams through its complexities, then the aspiration for developing excellence will never be attained.

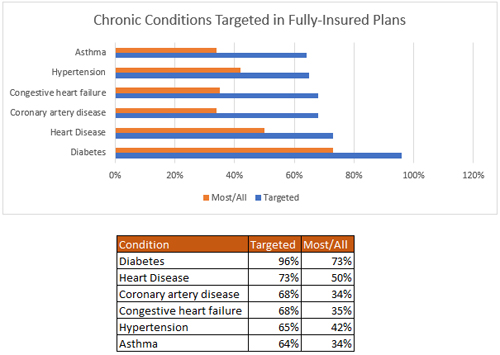

Block 2: Data-Driven Improvement

Evidence of what constitutes quality care is always evolving; this is a good thing for patients and the health of our communities. This necessitates that providers regularly re-evaluate and change their practices in order to stay current (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2018). This, of course, assumes that this evidence will lead to improved patient care and outcomes. The challenge is typically about finding a balance regarding data. When making choices about care practices, too much data becomes daunting, too little leads to uncertainty. The goal is to hit a sweet spot where all members of the team feel like they have enough data to make informed decisions to enhance clinical excellence (Coppersmith, Sarkar, & Chen, 2019).

Block 3: Empanelment

Empanelment is a foundational strategy for building or improving primary health care systems by linking patients to a primary care provider. This strategy is a “critical pathway” for achieving optimal outcomes, effective universal health coverage, and population health management (Bearden, Ratcliffe, Sugarman, Bitton, & Anaman, 2019). To effectively promote patient engagement or, in some circumstances, patient re-engagement, the care team must remain coordinated, data must be up to date, and patient coordination and communication consistent. These elements are essential for excellence in primary care (McGough, Chaudhari, El-Attar, & Yung, 2018).

Block 4: Team-Based Care

The concept of a team approach in primary care is not new. However, it is often assumed that it is occurring. And though team-based care may occur, few organizations effectively and regularly evaluate its success and consider how their care teams might become even higher-performing. Namely, organizations should assess whether the required knowledge, skills, and abilities are present on the team (Larson, 2009), the team members are in their optimal roles (Luig, Asselin, Sharma, & Campbell-Schererand, 2018), and the team is striving for improvement together (Shukor, Edelman, Brown, & Rivard, 2018).

The identity of High-Quality, Comprehensive Primary Care, mid- and post-COVID

The past year and a half of providing care in a pandemic has starkly highlighted the importance of primary care. “During a pandemic, primary care is the first line of defense. It is able to reinforce public health messages, help patients manage at home, and identify those in need of hospital care” (Krist, DeVoe, Cheng, Ehrlich, & Jones, 2020).

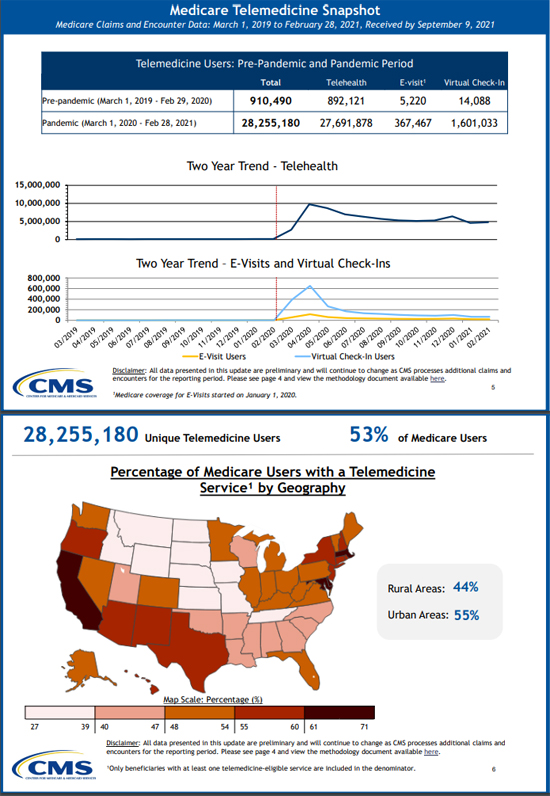

At the onset of the pandemic, primary care was forced to transform from a person-visiting-a-clinic modality to a telemedicine program (Jaklevic, 2020). Interestingly, healthcare systems and primary care practices had tried to coax this change prior to the pandemic, but many experienced resistance. The reasons for this resistance were complex and varied, yet literally overnight these changes occurred (Nittari, Khuman, Baldoni, Pallotta, Battineni, et al, 2020; Kaplan, 2020). Some would say the change occurred too quickly.

Initially, these programs demonstrated success with continuity of care, improved or plateaued outcomes, and reimbursement from payers (Rosen, Joffe, & Kelz, 2020). However, cracks present within team cohesion before the pandemic combined with overnight forced change highlighted vulnerabilities and tension in teams that were inadequately lead, staffed, managed, and skilled. It is evident that while teams with the aforementioned gaps struggled or continue to struggle today, high-performing teams pre-pandemic continued to transition successfully (Contreras, Baykal, & Abid, 2020).

The characteristics of high-quality primary care in the midst of COVID and post-COVID requires providers to get back to basics. Providers need to set their sights on the quadruple aim of enhancing the care experience, improving the health of the population, reducing costs, and improving the work-life of the team, as well as ensuring that the foundational building blocks of the Bodenheimer model are firmly in place.

Health systems must invest in the primary care infrastructure. This begins with team leadership that endorses engagement and satisfaction, sufficient and easily-accessible data, the appropriate application of a patient panel that promotes appropriate ratio of patient acuity that leads to population health management in and out of the clinic, and a fully staffed team that fosters cohesion, camaraderie, and continual desire to improve.

Read more from Dr. Seleem Choudhury at seleemchoudhury.com

Reference

American Association of Retired Persons Chronic Conditions among Older Americans. https://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/health/beyond_50_hcr_conditions.pdf.

Bearden, T., Ratcliffe, H. L., Sugarman, J. R., Bitton, A., Anaman, L. A., Buckle, G., Cham, M., Chong Woei Quan, D., Ismail, F., Jargalsaikhan, B., Lim, W., Mohammad, N. M., Morrison, I., Norov, B., Oh, J., Riimaadai, G., Sararaks, S., & Hirschhorn, L. R. (2019). Empanelment: A foundational component of primary health care. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7134391/

Bodenheimer, T., Ghorob, A., Willard-Grace, R., & Grumbach, K. (2014). The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Annals of family medicine, 12(2), 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1616

Braillard, O., Slama-Chaudhry, A., Joly, C., Perone, N., & Beran, D. (2018). The impact of chronic disease management on primary care doctors in Switzerland: a qualitative study. BMC family practice, 19(1), 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0833-3

Coppersmith, N. A., Sarkar, I. N., & Chen, E. S. (2019). Quality Informatics: The Convergence of Healthcare Data, Analytics, and Clinical Excellence. Applied clinical informatics, 10(2), 272–277. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1685221

Contreras, F., Baykal, E., & Abid, G. (2020). E-leadership and teleworking in times of COVID-19 and beyond: what we know and where do we go. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3484. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590271/full

Hahn, K. A., Gonzalez, M. M., Etz, R. S., & Crabtree, B. F. (2014). National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) patient-centered medical home (PCMH) recognition is suboptimal even among innovative primary care practices. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 27(3), 312-313. https://www.jabfm.org/content/27/3/312.full

Haverfield, M.C., Tierney, A., Schwartz, R. et al. Can Patient–Provider Interpersonal Interventions Achieve the Quadruple Aim of Healthcare? A Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 2107–2117 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05525-2

Fried L. America’s Health and Health Care Depend on Preventing Chronic Disease. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/americas-health-and-healthcare-depends-on-preventing_us_58c0649de4b070e55af9eade

Jaklevic MC. Telephone Visits Surge During the Pandemic, but Will They Last? JAMA. 2020;324(16):1593–1595. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2771681

Key Driver 2: Implement a Data-driven Quality Improvement Process to Integrate Evidence into Practice Procedures. Content last reviewed November 2018. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/evidencenow/tools/keydrivers/implement-qi.html

Krist, A. H., DeVoe, J. E., Cheng, A., Ehrlich, T., & Jones, S. M. (2020). Redesigning Primary Care to Address the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Midst of the Pandemic. Annals of family medicine, 18(4), 349–354. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7358035/

Kaplan, B. (2020). Revisting health information technology ethical, legal, and social issues and evaluation: telehealth/telemedicine and COVID-19. International journal of medical informatics, 104239. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1386505620309382

Larson Jr, J. R. (2013). In search of synergy in small group performance. Psychology Press.

Luig, T., Asselin, J., Sharma, A. M., & Campbell-Scherer, D. L. (2018). Understanding implementation of complex interventions in primary care teams. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 31(3), 431-444. https://www.jabfm.org/content/31/3/431.short

Murtagh, S., McCombe, G., Broughan, J., Carroll, Á., Casey, M., Harrold, Á., … Cullen, W. (2021). Integrating Primary and Secondary Care to Enhance Chronic Disease Management: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Integrated Care, 21(1), 4. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5508

Nittari, G., Khuman, R., Baldoni, S., Pallotta, G., Battineni, G., Sirignano, A., ... & Ricci, G. (2020). Telemedicine practice: review of the current ethical and legal challenges. Telemedicine and e-Health, 26(12), 1427-1437.

Pariser, P., Pham, T. N. T., Brown, J. B., Stewart, M., & Charles, J. (2019). Connecting people with multimorbidity to interprofessional teams using telemedicine. The Annals of Family Medicine, 17(Suppl 1), S57-S62. https://www.annfammed.org/content/17/Suppl_1/S57.short

Peterson Center on Health Care, & Stanford Medicine Clinical Excellence Research Center. America’s Most Valuable Care: Primary Care; 2014. https://petersonhealthcare.org/americas-most-valuable-care

Qureshi, N., Quigley, D. D., & Hays, R. D. (2020). Nationwide Qualitative Study of Practice Leader Perspectives on What It Takes to Transform into a Patient-Centered Medical Home. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(12), 3501-3509. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11606-020-06052-1

McGough, P., Chaudhari, V., El-Attar, S., & Yung, P. (2018, June). A health system’s journey toward better population health through empanelment and panel management. In Healthcare (Vol. 6, No. 2, p. 66). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.

Reynolds, R., Dennis, S., Hasan, I. et al. A systematic review of chronic disease management interventions in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 19, 11 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0692-3

Rosen, C. B., Joffe, S., & Kelz, R. R. (2020). COVID-19 Moves Medicine into a Virtual Space: A Paradigm Shift From Touch to Talk to Establish Trust. Annals of surgery, 272(2), e159–e160. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7268874/

Rothman A, Wagner EH. Chronic iIllness management: what is the role of primary care?. Ann Intern Med. 2003. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00034.

Safety Net Medical Home Initiative. Altman Dautoff D, Philips KE, Manning C. Engaged Leadership: Strategies for Guiding PCMH Transformation. In: Phillips KE, Weir V, eds. Safety Net Medical Home Initiative Implementation Guide Series. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: Qualis Health and The MacColl Center for Health Care Innovation at the Group Health Research Institute; 2013. https://www.safetynetmedicalhome.org/sites/default/files/Implementation-Guide-Engaged-Leadership.pdf

Shukor, A. R., Edelman, S., Brown, D., & Rivard, C. (2018). Developing community-based primary health care for complex and vulnerable populations in the Vancouver Coastal Health region: HealthConnection Clinic. The Permanente Journal, 22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6141648/

Tinker A. How to Improve Patient Outcomes for Chronic Diseases and Comorbidities. [(accessed on 30 December 2017)]; Available online: http://www.healthcatalyst.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/How-to-Improve-Patient-Outcomes.pdf

Share This Post

Share This Post